The Oromo Migrations, Abba Bahrey’s Witness, and the Fate of Pre-Oromo Populations

By Eshetu Mekonnen

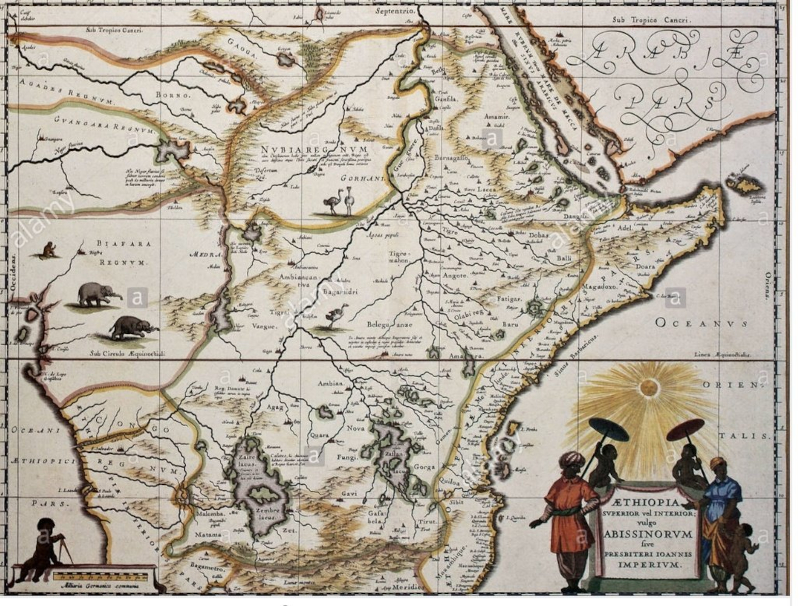

The Oromo migrations of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries are among the most consequential population movements in the Horn of Africa. They reshaped the demographic, political, and cultural map of Ethiopia so thoroughly that many of the peoples who once inhabited the central and southern highlands either disappeared, became fragmented, or were absorbed into the expanding Oromo identity. To understand these transformations, especially from the perspective of descendants of the pre-Oromo populations, we must begin with the historical conditions that enabled the migrations, examine how contemporaries like Abba Bahrey viewed them, and analyze the far-reaching political consequences that followed.

I. Background: Conditions That Enabled the Migrations

The Oromo migrations began in the early sixteenth century in the region south of the Ethiopian highlands, near the Jubba, Ganale, and Dawa rivers. At that time, the Oromo were organized into pastoral and semi-pastoral societies governed by the gadaa system, which regulated political authority, military activity, and generational leadership. The Ethiopian highlands to the north, meanwhile, were weakened by the destructive wars between the Christian kingdom and Imam Ahmad Gragn (1529–1543). The collapse of older power structures, the depopulation of fertile areas, and the fragmentation of long-standing polities created an unstable frontier.

It was into this vacuum that Oromo groups advanced. They followed two major routes into Ethiopia: one through Bale and Arsi into Shewa, another through Borana and Guji into Welega and the western highlands. The result was not a single invasion but a sustained, multi-generational expansion that brought Oromo clans into contact, and often conflict, with Sidama-related populations, Omotic-speaking groups, Hadiyya remnants, Argobba communities, and earlier Cushitic chiefdoms.

II. Abba Bahrey: The Eye-Witness Historian of the Migrations

To grasp how the migrations unfolded as lived experience, the most crucial primary source is Abba Bahrey (Bahri), a monk and scholar who wrote “Zenahu le Galla” (“The History of the Galla/Oromo”) in 1593. Bahrey was not a distant chronicler; he was witnessing the rapid transformation of entire regions around him.

Bahrey begins by describing Ethiopia as a land already destabilized by previous wars, its population diminished and its institutions weakened. Into this fragile landscape, Oromo clans advanced with a momentum that astonished him. He emphasizes three qualities of their expansion: speed, persistence, and disruption. The Oromo did not move slowly nor sporadically. They advanced in coordinated Luba age groups. When a generation completed its gadaa duties, a new one immediately replaced it, creating a sense of an endless human tide.

Bahrey’s narrative paints a stark picture of resistance and collapse. He recounts how inhabitants of Shewa fortified themselves in hilltop settlements, how Sidama chiefdoms in Bale and Arsi attempted to repel the newcomers, and how Omotic groups in Welega retreated repeatedly. Yet every victory against the Oromo was temporary. New waves soon followed, overwhelming communities that lacked the manpower or political cohesion to maintain prolonged resistance.

Most striking in Bahrey’s account is his repeated observation that entire districts were emptied of their original inhabitants and refilled by Oromo settlers. Villages disappeared. Place names were replaced. Populations fled northward or into forests. Some groups vanished so completely that, beyond scattered medieval references, they left no trace in later Ethiopian ethnography.

For Bahrey, this was not cultural blending; it was the dissolution of existing societies. The migrations represented, in his view, a fundamental reordering of the Ethiopian highlands, a demographic revolution whose effects would be permanent.

III. Forced Displacement: A Widespread Structural Process

From the perspective of descendants of the pre-Oromo populations, the migrations must be understood not as peaceful cultural diffusion but as a series of forced displacements, territorial losses, and coerced incorporations.

Historical and anthropological evidence supports Bahrey’s account. According to Mohammed Hassen, the early Oromo advances repeatedly pushed out Sidama groups from Arsi and Shewa, and many were forced to migrate into marginal environments. Merid Wolde Aregay likewise notes the fragmentation and disappearance of Cushitic-speaking communities that medieval chronicles once described as major populations in the central highlands. Ulrich Braukämper documents the scattering of Hadiyya subgroups and the dissolution of their political institutions. Christopher Ehret shows how Omotic populations were driven from fertile agricultural zones into forests or peripheral regions.

Displacement in this context did not simply involve leaving one’s village. It meant the collapse of entire social orders:

- loss of ancestral land

- fragmentation of kinship networks

- abandonment of political institutions

- loss of identity continuity

- falling into servitude or dependence in new territories

Many groups fled northward toward the Christian highlands seeking protection. Others merged with displaced peoples elsewhere. Some disappeared entirely.

IV. Subjugation and Enforced Assimilation

Even when populations were not physically expelled, they were often drawn into unequal power relationships with the expanding Oromo groups. Abba Bahrey’s descriptions of tribute, submission, and political domination correspond to what scholars later identify as moggaasa, the incorporation of defeated or vulnerable groups into Oromo clans.

But this incorporation was not typically consensual. It required subordinate groups to:

- abandon their original identities

- adopt Oromo clan names

- accept Oromo land laws and dispute systems

- pay tribute

- become clients (gabbaro) under Oromo authority

Assimilation unfolded through pressure, dependency, and generational erosion of alternative identities. Over time, the distinction between conqueror and conquered blurred, but only after the conquered had relinquished their autonomy.

V. The Disappearance of Indigenous Peoples

Perhaps the most politically significant outcome of the migrations is the erasure of entire populations. The peoples who resisted most strongly were often the first to disappear. Those who were forcibly scattered could not reproduce the political institutions necessary to maintain ethnic continuity. Women and children from defeated communities were absorbed into Oromo lineages; their descendants became Oromo regardless of origin.

Bahrey’s testimony is corroborated by later scholars who note that several ethnic names appearing in medieval Ethiopian sources vanish entirely after the sixteenth century. These disappearances cannot be explained by peaceful blending. They reflect the cumulative effects of:

- repeated conflict

- displacement from ancestral lands

- loss of leadership

- forced incorporation

- linguistic domination by Afaan Oromo

- erasure of oral traditions

The modern absence of these peoples from Ethiopia’s ethnographic record is itself a historical consequence of the migrations.

VI. Political Silence and Long-Term Consequences

The final stage of displacement is political silence. By the time the Ethiopian empire expanded southward in the nineteenth century, the pre-Oromo populations of central Ethiopia no longer existed as coherent groups. The imperial state negotiated with Oromo authorities, not the descendants of those who had resisted them centuries earlier.

This has had lasting effects on modern Ethiopian politics:

- The regions transformed by the migrations are remembered as historically Oromo, because no earlier groups survived intact to contest the narrative.

- Ethnic federalism today reflects identities that endured, not those erased.

- Claims to ancestral homelands lack representation from peoples whose histories were cut short in the sixteenth century.

From the viewpoint of descendants of the assimilated or displaced groups, the Oromo migrations were not merely demographic movement but a political reordering of the highlands that eliminated alternative identities.

VII. Conclusion: A Critical Historical Perspective

A critical analysis of the Oromo migrations, especially when informed by Abba Bahrey’s eyewitness testimony, reveals that the process involved not only cultural incorporation but also sustained episodes of violence, displacement, subjugation, and the erasure of entire populations. This does not assign moral blame to one group or absolve another; rather, it situates Ethiopian history within global patterns of migration and expansion, where the rise of one identity often requires the disappearance or subordination of others.

Understanding this history is essential for interpreting Ethiopia’s present. Modern political identities are built upon the remnants of processes that reshaped the highlands centuries ago. Recognizing the complexity of that past, including the voices of those who were displaced or absorbed, allows for a deeper and more honest engagement with contemporary debates about land, identity, and historical memory.

References

- Abba Bahrey, Zenahu le Galla.

- Mohammed Hassen, The Oromo of Ethiopia: A History 1570–1860.

- Merid Wolde Aregay, The People of the Red Sea and the Ethiopian Highlands.

- Ulrich Braukämper, History of the Hadiyya People of Southern Ethiopia.

- Christopher Ehret, History and the Peoples of the Horn of Africa.

- J. Spencer Trimingham, Islam in Ethiopia.

- Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia.

- Donald N. Levine, Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society.

- Harold Marcus, A History of Ethiopia.

- G.W.B. Huntingford, The Galla of Ethiopia.

- Paul Baxter, Gadaa: The Oromo Traditional System of Government.

Opinions expressed by contributors are their own. Ethiofact does not endorse and is not responsible for the accuracy of any of the views expressed in the content on this site.